The Aura of Kony Island

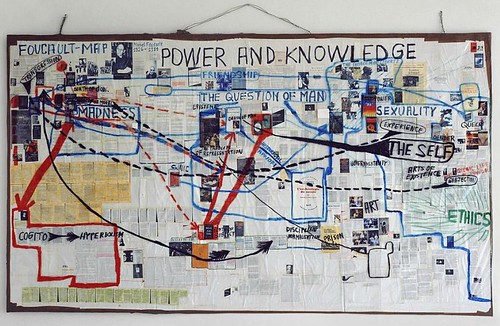

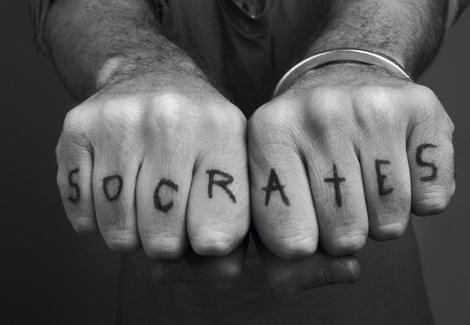

What is our present? What is the present field of possible experiences? This is not an analytics of truth; it will concern what might be called an ontology of the present, an ontology of ourselves, and it seems to me that the philosophical choice confronting us today is this: one may opt for a critical philosophy that will present itself as an analytic philosophy of truth in general, or one may opt for a critical thought that will take the form of an ontology of ourselves, an ontology of the present…

At the risk of responding heedlessly, I venture that our present is defined by the humanitarian pleasure principle. We live in

an age of drone aesthetics – every grain of geographic space, every gesture of

lived reality, every click of pleasurable association records and cites a

historicized datum of our contemporary mode of existence. The mediated flow of

images flourishes while the world passes away.

Consequently, those who resist or rebel against a form of power cannot merely be content to denounce violence or criticize an institution. Nor is it enough to cast the blame on reason in general. What has to be questioned is the form of rationality at stake…The question is: how are such relations of power rationalized? Asking it is the only way to avoid other institutions, with the same objectives and the same effects, from taking their stead.

We sit idly trapped in the muddied trenches of an uncanny valley – a horizon of existence bereft of the eternal gloss of the nation state, the species, religion and republic. The variegated spectrum of forms by which political associations and ethical commitments take place has outstripped the potentiality for the taxonomic nodes to retain their positions as meaningful referents. When politics is reduced down to a distracted display of public affiliation, the capacity for change becomes impotent.

The Kony 2012 Campaign which has recently gone viral offers

a keen case study evincing the means by which the politics of humanitarianism

short circuits the perceived necessity of, the capacity to, and the desire for

a reflexively engaged ethico-political constitution of the global citizen.

Right now there are more people on Facebook, than there were on the planet 200 years ago. Humanity’s greatest desire is to belong and connect. And now we see each other, we hear each other…we share what we love and it reminds us what we all have in common… (Kony2012)

Benjamin continues in Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproducibility:

The desire of the present-day masses to “get closer” to things spatially and humanly, and their equally passionate concern for overcoming each thing’s uniqueness by assimilating it as a reproduction….The stripping of the veil from the object, the destruction of the aura, is the signature of a perception whose “sense for sameness in the world” has so increased that, by means of reproduction, it extracts sameness from what is unique (255-6).

The introduction’s statement that, “Humanity’s greatest

desire is to belong and connect" performs, analyzes and describes the process

by which the increasing significance of the masses is linked to the desire to

overcome uniqueness. To reproduce the work of art through the youtube film

means to merely share it; the work’s reproduction coincides with its

consumption. Thus the dynamics of the artwork’s aura have reinvigorated their

original ritualistic association.

As Benjamin writes:

As Benjamin writes:

The unique value of the “authentic” work of art has its basis in ritual, the source of its original use value.

Markers of the viral-ity of the video, the display of

the statistics of views, analytics, data etc…express the thoroughness of “the

interpenetration of art and science” in the age of technological

reproducibility. The ritual is disclosed through the knowledge of the commonality

of viewership which simultaneously endows a video with a cult like magic, while

depressing any semblance of uniqueness inherent in the act of consumption.

The video then proceeds to show a scene of a person who ‘hears’

for the first time as the result of a cochlear implant. In seeing another

person learn to hear, we learn to see hearing differently, and hear different

things than were previously possible. The film discloses a world of scenes and

gestures contained within our everyday movements that were previously unknown. Film calls for our attention and analysis because it more precisely documents the

gestures of the body, through slow motion time is extended, through the

juxtaposition of images new associations emerge, through the procession of

angles new viewpoints and understandings of positionality are created and so

on.

Photographic records begin to be evidence in the historical trial. This constitutes their hidden political significance. They demand a specific kind of reception. Free-floating contemplation is no longer appropriate to them. They unsettle the viewer; he feels challenged to find a particular way to approach them.

Watching the cursor click share leads to an instinctive, mimetic desire to also share the video, perceptions and understandings of the video are changed in the act of consumption itself.

“The world is changing…the rules of the game have changed…the next 27 minutes are an experiment, but in order for it to work you have to pay attention" (Kony 2012)

“[T]he audience is an examiner, but a distracted one” (Benjamin).

Labels: Audience theory, cyber rhetoric, humanitarianism, Joseph Kony, Kony 2012, Michel Foucault, New Media, ontology, P, Walter Benjamin, Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproducibility