On the University of Chicago's Theories of Media online glossary Sarah Coffey offers

an interesting genealogical mapping of the concept of prosthesis. The glossary and Coffey's essay itself performs the concept itself.

Combining the Latin pro (forward) with thesis (stressed syllable), prosthetics denotes addition or extension. The OED defines "prosthetics" in its plural form as "the branch of surgery concerned with the replacement of defective or absent parts of the body by artificial substitutes." "Prosthetic" derives from the word "prosthesis," which can refer to the addition of a syllable or letter at the beginning of a word, or to surgical prosthesis. The shift from the literal connotation of grammatical prosthesis to the figurative connotation of surgical prosthetics took place in the 16th century, when "prosthesis" was adopted by medical terminology to denote the substitution of an artificial body part for missing limbs or teeth (Jain 32). This article will examine prosthetics in reference to both the actual extension of the body by artificial means, and the virtual extension of the body by various forms of media.

Media theory examines the double meaning of prosthetics, as simultaneously supplementing a deficiency and signaling deficiency in the object to which it is supplied. In Marshall McLuhan's seminal text, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, he uses the concept of prosthesis to explain media's function as "any extension of ourselves" (7). Stressing the physicality of media extensions, McLuhan describes the wheel as an extension of the foot, clothing as an extension of the skin, and electric technology as an extension of the central nervous system. Yet as media extends, it also amputates. Although electric technology extends the central nervous system, "such amplification is bearable by the nervous system only through numbness or blocking of perception" (McLuhan 43). Thus McLuhan asserts that a process he terms "autoamputation" accompanies any extension of media.

Prosthesis is a

doing, a making, and a placing of the supplement. The addition to bodies

includes something previously existing outside itself. Prosthesis ruptures the

relations between man’s tripartite divisions, psyche, soma and soul. Yet in

modern times, it has become not simply an addition but a replacement.

Prosthesis begins to work by removing the previously deviant aspects of man’s

existence. A reconstitution of ability inaugurated in the shadow of man’s

uncanny wounded self.

Does posthistorical man create the edifices like birds

build nests, as Kojeve posits? Out of the question itself emerges the

definitive characteristic of man, defined not in terms of attributes but an

imperative, to know thyself through experimental investigation. Whereas

disability, disease and madness previously were seen as a source of disclosing

truths hitherto unknown to average man, in modernity, disability is exhausted of

its vital force “by way of investment in believing that disability makes a

person available for excessive experiment” (Snyder & Mitchell, 37). Man’s

“speculation parading as empiricism” is most intense and uncertain at the

limits of the anomalous body. “cultures thrive on solving the riddle of

disability’s rhyme and reason” (25).

In this sense Agamben’s work offers a

promising site for investigating the disabled body. Politics in modern times

has been depoliticized, emptied of its life force, by reducing the question of

politics, history and ethics to a preordained reaction, not response, to the

injunction to end suffering, cure the pathology, or fulfill the abstract

containers of ‘human’ rights. The inability to reconcile the disabled body with

the defining characteristics of man’s constitution performs an “interruptive

labor” (53). The internal divisions of man are exposed as the conditions of

possibility for any limit to be drawn between the human and non-human, as the

fuel for the anthropological machine’s fire.

Labels: critical animal studies, Critical Disability Studies, disability, Giorgio Agamben, Media Theory, non-human, Posthumanism, Prosthesis, Susan Coffey

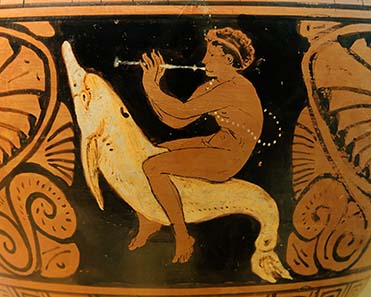

Yet, the situation isn't completely overdetermined by the drudges of despair; one may always flee from the imposed order of an alien selfhood, take a topsy-turvy turn, deciding without judgment between madness disclosed as melancholy or the mayhem delivered as a melody. A melody completely unknown to the Athenian flute player of Aristotelian teleology, or the Corp of Drums when the sun refused to set on the British Empire and composed of barely beyond boyhood drummers, learning and giving the orders of warfare, where comprehension of the threshold of play, when the drum beat's dance between wooden member and raw hide head ceases to play but becomes an unthought extension of a heart stuck in the violent oscillations of a warrior resonance.

Yet, the situation isn't completely overdetermined by the drudges of despair; one may always flee from the imposed order of an alien selfhood, take a topsy-turvy turn, deciding without judgment between madness disclosed as melancholy or the mayhem delivered as a melody. A melody completely unknown to the Athenian flute player of Aristotelian teleology, or the Corp of Drums when the sun refused to set on the British Empire and composed of barely beyond boyhood drummers, learning and giving the orders of warfare, where comprehension of the threshold of play, when the drum beat's dance between wooden member and raw hide head ceases to play but becomes an unthought extension of a heart stuck in the violent oscillations of a warrior resonance.