Towards a Thinking-Feeling Cultural Theory

Jenny Edbauer defines affect as “the experience of having the ground pulled out from under our feet” (11). This reminds me of the old Tom and Jerry or Wiley Coyote cartoons in which a character runs off the cliff but does not fall until they realize that they are no longer standing on solid ground. There is a split second in which the character still attempts to run and move before they realize they have been slighted. There is a break in the narrative of the chase. There is a moment in which a sense of shock is registered and visibly felt before the character falls.

Edbauer offers several other illuminating ways to theorize affect: “as the sensation of the periphery” (12), “a feeling of excess and exposure” (13), and “the experience of relationality” (13). The mixture of characterizations (sensation, feeling, experience) demonstrates the ways that affect is an irreducible force. It is a challenge to commonsense modes of understanding subjectivity. It shows us that “we are not a/lone(ly), but that we exist in relations beyond what we may recognize or even wish” (11) and that we “already exist in zones of indetermination” (16). Conceiving of the self as existing always already in relation transforms the grounds upon which cultural theory can analyze why subjects develop attachments within the realm of ideology or qualification.

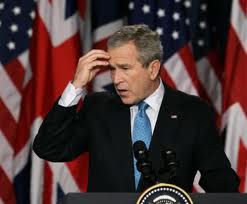

Edbauer offers several other illuminating ways to theorize affect: “as the sensation of the periphery” (12), “a feeling of excess and exposure” (13), and “the experience of relationality” (13). The mixture of characterizations (sensation, feeling, experience) demonstrates the ways that affect is an irreducible force. It is a challenge to commonsense modes of understanding subjectivity. It shows us that “we are not a/lone(ly), but that we exist in relations beyond what we may recognize or even wish” (11) and that we “already exist in zones of indetermination” (16). Conceiving of the self as existing always already in relation transforms the grounds upon which cultural theory can analyze why subjects develop attachments within the realm of ideology or qualification. Edbauer also shows the ways in which affect is an impersonal and social force. (14) Since affect is something that precedes indexical qualification or cognitive interpretation “The visceral registering of excess is not necessarily a positive or negative phenomenon” (20). For these reasons Edbauer offers an alternative interpretation to understand why Bush’s fumbling speeches actually move people. She writes, “Before we can like, love, or loathe Bush—before the space of critique is even opened to us—we encounter his potential for affect(ation)” (16). We are “sensually involved” (16) in our experience of the Presidential event in such a way that we cannot stay removed.

Bush is an exemplary case for Edbauder because the so-called Bushisms are perfect demonstrations of the ways in which cultural theory’s representational or ideological explanations alone are insufficient. While Bush’s speaking ability in many ways is opposite of Teflon Ron’s, there is a similar dynamic at work in both. Although, Massumi’s citing of Oliver Sacks’ work challenges certain conceptions of Reagan as the Great Communicator, there is still an obvious difference in the polished or professional quality of their mannerisms. Massumi sees Reagan’s jerky movements and erratic rhythms of speech not as deficiencies but supplementary communicative forces. The affective events that implicate the audience in Reagan’s speeches were the reason why he could be so many things to so many people.

Bush is an exemplary case for Edbauder because the so-called Bushisms are perfect demonstrations of the ways in which cultural theory’s representational or ideological explanations alone are insufficient. While Bush’s speaking ability in many ways is opposite of Teflon Ron’s, there is a similar dynamic at work in both. Although, Massumi’s citing of Oliver Sacks’ work challenges certain conceptions of Reagan as the Great Communicator, there is still an obvious difference in the polished or professional quality of their mannerisms. Massumi sees Reagan’s jerky movements and erratic rhythms of speech not as deficiencies but supplementary communicative forces. The affective events that implicate the audience in Reagan’s speeches were the reason why he could be so many things to so many people.  In many respects I find Massumi’s explanation for why Reagan moved people much more satisfactory than Edbauer’s explanation for Bush. While she does a great job of descriptively translating Bush’s idiosyncrasies into the vocabulary of affect theory, I’m still left wondering about exactly what is the specific connection between Bush’s jolts and the audience’s experience. Reagan was a very popular figure among people while Bush was seen in a less than favorable light. I’m not sure that Bush even really moved many people in his speeches.

In many respects I find Massumi’s explanation for why Reagan moved people much more satisfactory than Edbauer’s explanation for Bush. While she does a great job of descriptively translating Bush’s idiosyncrasies into the vocabulary of affect theory, I’m still left wondering about exactly what is the specific connection between Bush’s jolts and the audience’s experience. Reagan was a very popular figure among people while Bush was seen in a less than favorable light. I’m not sure that Bush even really moved many people in his speeches. Edbauer writes that, “Bush hacks our experience of narrative so easily, and with such a degree of intensity, because we are already in a kind of relationality with this executive body” (12). What sort of relationality are we already in with Bush? After listening to speeches from Bush during multiple campaigns and speech conferences are the interruptions really that interrupting? In other words, after Bushisms become a predictable part of his narrative do the “incorrect statements, tautologies, malapropisms, mispronunciations, and bewilderings remarks” (6) really “stage a jolt, causing intensity to build around them” (6)? Or are audiences so used to them that they glide over the surface of the skin relatively unnoticed? I think that Edbauer would say that the question is not whether they are cognitively registered but what these sticky associations do in experience of the Executive body. Is it just the fact that there are jolts and interruptions that “exposes the “productivity” of affect as a relational capacity” (7)? It’s difficult for me to reconcile the idea of affect as impersonal yet always already social.

It is here that I would like to compare Edbauer’s account of affect with a reading of Kristeva’s work on affect. I’m not sure exactly if Edbauer would disagree with all of it, but in the very least I think it offers an additional way of theorizing the question. I think that Kristeva’s reading of Plato’s chora from the Timaeus very closely resembles a lot of writings surrounding affect studies. The chora is the third principle that mediates the between matter and ideas. It is understood as a sort of receptacle or maternal space. Cecilia Sjoholm in “Kristeva & the Political” (2005) writes,

The chora is the space outside of being because it engenders transformation, mobility, motility, novelty, not a psychic site but a site of investments. Although it may be a container of affects and memories, it is not immediately translatable as the body, but rather the quasi-transcendental condition that makes corporeal mediation possible. The chora is a term of mediation irreducible to the terms of negativity and signification, not governed by law, but by a kind of organization. (19)

Much of this description of the chora is similar to the ways that Edbauer and Massumi describe the necessary condition of potentiality that allows affects to emerge, transfer, and transform. The above description attempts to distinguish the chora from theories of affect that conceive of affect in a reductionist manner as directly translatable to bodily experience. I think that the ways that Edbauer describes the process of thinking-feeling demonstrates that Sjoholm’s distinction is not applicable to her account. Another one of Sjoholm’s definitions of the chora is strikingly similar to descriptions of affect, “that which cannot be named but shown in the form of rhythm, form, excess” (19). The chora is the space of generativity and poesis, the irreducible zone of indiscernability in which “the alterity of the other will make itself known through the excesses of signification known as the semiotic” (19).

Much of this description of the chora is similar to the ways that Edbauer and Massumi describe the necessary condition of potentiality that allows affects to emerge, transfer, and transform. The above description attempts to distinguish the chora from theories of affect that conceive of affect in a reductionist manner as directly translatable to bodily experience. I think that the ways that Edbauer describes the process of thinking-feeling demonstrates that Sjoholm’s distinction is not applicable to her account. Another one of Sjoholm’s definitions of the chora is strikingly similar to descriptions of affect, “that which cannot be named but shown in the form of rhythm, form, excess” (19). The chora is the space of generativity and poesis, the irreducible zone of indiscernability in which “the alterity of the other will make itself known through the excesses of signification known as the semiotic” (19).Sara Ahmed’s essay “The Skin of the Community: Affect and Boundary Formation” in the collection “revolt, affect, collectivity: the unstable boundaries of kristeva’s polis” also offers an interesting account of affect to dovetail with Edbauer’s. I think her account can help explain some of the reasons why Bush moves people, but perhaps at the expense of giving up too much ground to explanations that exist within the realm of meaning. Ahmed writes,

The transformation of this or that other into a border object is over-determined. It is not simply any body that becomes the border; particular histories are reopened in each encounter, such that some bodies are already read as more hateful and disgusting than other bodies. Histories are bound up with attachments precisely insofar as it is a question of what sticks, of what connections are lived as the most intense or intimate, as being closer to the skin. Such an encounter moves us both sideways and forwards and backwards (the histories that are already in place that allow these associations and not others stick, and that allow them to surface in memory and writing) (106).

I find it hard to account for the reasons why Bush move’s people without bringing in the question of memories and histories in relation to the Executive body. It seems that Edbauer is so concerned with theorizing affect as purified from the realm of meaning that it comes at the expense of analyzing contextual factors influencing people’s experience of Bush. The sticky associations surrounding the speaker such can act as blockages or heightened sensitivities to the affective forces of a speech in ways that lead to dramatically different experiences on the part of the audience. While I agree with the importance in situating affect as preexisting the grid of ideological et. al. forces, I think it is likewise impossible to leave these factors out. I also do not mean to do an injustice to Edbauer’s theory in my reading of it and simply criticizing it for leaving something out. I think that this is a question she is conscious of when she writes, “this is not to say that the sensual experience of affect marks a return to a primal scene of origination” (16). Nonetheless, perhaps this is simply begging the entire question of affect studies that continues to haunt me. Which is how can a theory of affect toe the threshold between talking about something which exceeds qualification yet productively analyze its force without qualifying it. The aporia strikes back.

Labels: Affect, Bush, Cecilia Sjoholm, Chora, Cultural Theory, Jenny Edbauer, Kristeva, Massumi, Reagan, Sara Ahmed