Intro:

Cascading waves larger than Japan’s tsunami will crash down, bubbles will burst with the force of supernovae, and the streets will run red with the ink of a budget in deficit if Americans don’t fix the debt crisis, or so we’re told. The current debate over how to fix the U.S. budget dilemma swarms with a passionate rhetoric of crisis, victimization, and shame as lawmakers define the borders of concern. For my project I will undertake an aesthetico-politcal mapping of the affective intensities that compose the public(s) surrounding the debt crisis. I will show how the various strategies employed in institutionalized discourse create collective imaginaries that are held in a precarious balance, subject to the swift flick of a legislation writing wrist.

The current debate occurs upon territories of feeling more so than disembodied cognition. While this characteristic is true of most American politics, it is especially germane to the budget issue for a few reasons. The tax code is a labyrinthine web of policy text that is abstract beyond most people’s comprehension, yet issues of dollars and sense remain intricately tied to deeply held values and questions of identity. The budget we choose determines who we are, take Obama’s budget speech for example “This is who we are. This is the America I know.” Furthermore, such a complex issue requires metaphors that simplify the issue in cognitive terms yet amplify its magnitude in affective force. The budget debate occurs on the limits and thresholds of political alignments, investments and cuts occur in relation to emotively charged goods that circulate not just as public benefits but as affective entities.

Adopting a rhetorical analysis that explores the dimensions of pathos and affect is especially poignant in the case at hand because of the nature of topic. While much of the institutional discourse dispersed centers on concrete effects of a particular plan, there is also a meta-commentary on the material effects of the budget and debt debate on financial markets. Lawmakers are faced with a situation in which their participation in the debate changes the conditions of the policy field itself.

Specifically, I will focus my analysis on the ways that the search for the wound circulates rhetorics of shame and victimization in order to translate abstract policy numbers onto emotively invested figures. Beyond being merely politically useful tropes, this move is part of a larger process of shifting the collective imagination of “the good life.” Austerity and sacrifice are posed as positive principles in response to the eschatological predictions of crisis. I will supplement this final aspect by demonstrating the ways that visual imagery, through graphs and charts become an increasingly effective tool for simplifying such a dizzying array of statistics. And finally, I will point to some of the larger implications such an analysis has for theorizing the operations of publics and the role of the critic.

Sara Ahmed theory of ‘affective economies’ is a useful analytic for understanding why feelings dance with figures. For Ahmed, affect is an impersonal force that swarms through networked spaces that precede the subject. She analogizes the movements of affects to the circulation of commodities. They accumulate a surplus of value or intensity through processes of exchange that conceal their histories, transformations, and origins. Ahmed offers a useful vocabulary for interpreting the recent budget and debt debates. Emotions are the sticky substances that mediate the individual-milieu couple. Ahmed writes, “the individual subject comes into being through its very alignment with the collective. It is the very failure of affect to be located in a subject or object that allows it to generate the surfaces of collective bodies (128).” Affect is in intimate contact with the realm of meaning, rather than existing completely external to it. This is because affects operate in order to define and arrange bodies within specific relations.

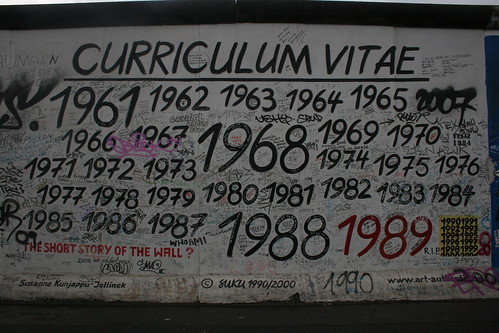

Ahmed writes on the tethering of catastrophe to character, “narratives of crisis are used within politics to justify a “return” to values and traditions that are perceived to be under threat.” There is a strange dialectic in which the fear of loss is always accompanied by what Lauren Berlant terms a ‘cruel optimism’ (93), or “the condition of maintaining an attachment to a problematic object in advance of its loss” (94). The budget (Politicians’ pork, peoples’ benefits and taxes) seems to be this frustrating endurance of an affective form par excellence. “Cruel optimism as an analytic lever,” for Berlant,“is an incitement to inhabit and to track the affective attachment to what we call “the good life” (97). The rhetoric of the budget debate gravitates toward appeals to futurity. Obama’s speech for example, “this doesn't have to be the country we leave to our children.” Fundamentally, it asks the question what sort of life do we want to reproduce and who is helping or hurting this cause.

The parallelism between the macro structures of spending and the everyday structures of feeling offers an insight into the economies of emotion. Economic analyst Kevin Drum writes “There are limits to how far a big country like the United States can get from fundamentals, but we're still susceptible to the kinds of mob emotion that power both bubbles and bank runs.” The value of austerity is instilled as an ethic for both our economic and rhetorical etiquette. There is the constant refrain of the necessity for an ‘adult conversation.’ Berlant writes, “All of the strikes and tea parties in response to the state’s demand for an austere sacrifice under the burden of shame tell us that this incitement for the public to become archaic as a public is not going down too easily.” The intense fears of populism, the crowd, or class warfare haunt the discussions in a way that shows the impossibility of austerity. Joshua Green writes that, “‘class warfare’ has that extra dimension of apocalyptic consequence and the undertone of victimization that work so well together even though they shouldn't, like sweet-and-sour soup.” (Joshua Green) The figure of the incompetent and unfair populist is tied to a dismantling of the very fabric of American life.

Obama said in his speech, “We will all need to make sacrifices. But we do not have to sacrifice the America we believe in.” The budget crisis forces us to rethink the way shame functions as the underbelly to the positively imbued value of austerity; and furthermore “to think of austerity in relation to claims that the vulnerable should recode loss as sacrifice and therefore produce an affective cushion to replace the loss of other material ones, which were both real and affective.”

Austerity becomes a way of coping with the stark realities of an uncertain future. Ahmed theorizes about how “the fear of degeneration as a mechanism for preserving social forms becomes associated more with some bodies than others.” The Right has been able to recode shame from the figure of the crony capitalist to the excessive politician or consumer. The Left sticks shame to those that would “tell families with children who have disabilities that they have to fend for themselves” or “abandon the fundamental commitment this country has kept for generations.” Obama makes responsibility not just a partisan thing but “patriotism.” Ahmed writes, “threat of such others to social forms (which are the materialization of norms) is represented as the threat of turning away from the values that will guarantee survival.” Here it becomes evident that threat operates not merely as tethered to an objective referent of economic crisis.

Threat is intensified not only by means of exaggeration but also by attaching itself to abstracted character forms and socialized values that circulate without being tied to particular objects. Anxiety sets in because the ambiguity about what investments are excessive or dangerous or the cuts that might affect the vulnerable comes with the fear of passing. Berlant says “It might be unbearable to discover how little one matters to the reproduction of life, but shame is just one of the many moods of affective relation that locates persons and groups in the anxiety of forging an idiom of response.” Shaming is part of the process of constituting subjectivities by defining a self or collectivity in terms of proximity to or alignment with objects of promise or peril.

Mapping this terrain of affective friction means that “one must embark on an analysis of rhetorical indirection as a way of thinking about the strange temporalities of projection into an enabling object that is also disabling” (95). Taxation or cuts in spending are this paradoxical object for the parties. This contradiction at the heart of affective objects provides a basis for extending Ahmed’s Marxist analogy of affective commodities in terms of Crisis Theory. Crisis goes back to the Proto Indo European root krinein meaning “to separate, divide, judge.” Is this not what occurs within the encounter and enactment of a cruel optimism? Enabling forms of enjoyment are separated from the disabling, a conception of the good life is judged against its threat.

As Marx himself put it “the simple form of metamorphosis comprises the possibility of crisis, we only say that in this form itself lies the possibility of the rupture and separation of essentially complimentary phases” (451). While Ahmed analyzes affect in relation to the M-C-M circuit, Marx indicates that in the entanglement of production and circulation (or the M-C-M and C-M-C circuits) in the reproduction of capital lays “a further developed possibility or abstract form of crisis” (455). Furthermore, the largest cause of crisis derives from capital’s tendency to over-accumulate, “to produce to the limit set by the productive forces…without any consideration for the actual limits of the market” (465). Affective crises or over-saturation occurs when their circulation is separated from how they are produced or when they threaten the matrix that renews their life force.

When affects are freed from referents they can circulate and thus accumulate force so freely that they can be redeployed to undermine their initial cause. Ahmed writes, “To declare a crisis is not “to make something out of nothing”…But the declaration of crisis reads that fact/figure/event and transforms it into a fetish object that then acquires a life of its own” (132). The crisis becomes a thing that grows larger than the sum of its parts. “Through designating something as already under threat in the present, that very thing becomes installed as “the truth,” which we must fight for in the future, a fight that is retrospectively understood to be a matter of life and death.” (132) For example the figure of the elderly at threat of losing their life support has become an oversaturated figure within the political landscape: the Left use it as a victimized figure because of the ways the Right has employed it previously.

The budget debate no longer becomes about numbers but how we align with this particular figure. The hyper-mediated figure of the elderly or the budget crisis-thing is an assemblage of so many hybrid forces that a crisis ensues for the audience to interpret how it fits within their conceptual horizon of the ‘good life.’

Another interesting parallel in the analogy is the way that affect is actually related to market dynamics. By analyzing the accounts of emotional tendencies in markets and stockbrokers we get an example in which cognitive activities feed-forward and back into feelings. As Couze Venn writes,

what passes for the most rational of economic activities…that in reality turns out to depend on ‘a feeling for the market’ mixed in with a whole range of in-the-moment experiences as well as cognitive calculations. What is striking, then, is the instantaneous correlation of every kind of ‘information’: facts, signals, rumours, news, mixed in with moods and emotional energies, enabling agents to participate in an activity in which all behave both as an individual and as an element of a collectivity. (Couze Venn 2010)

Labels: Affect, Affective Economics, austerity, Budget, crisis, cruel optimism, Debt, guilt, lauren berlant, sacrifice, Sara Ahmed, shame, victimization